Building forms and validation

In this post I'll be detailing how I approached form state management and validation for a side-project of mine, Urban Jungle.

Typically in side projects, I like identify problems and solve them in new ways. Often by doing this, I expand my repertoire of skills in a way that generalises to other problems I come across.

What's the problem we're solving?

Urban Jungle doesn't have that many forms, however I wanted to build an abstraction in React that would allow me to define a data schema in TypeScript and to have the abstraction provide strongly typed state management and validation in a way that afforded great editor auto completion.

I also wanted a clear separation of concerns - I didn't want to have my UI components know anything about the form state management or validation logic. For that reason, I wanted a separate library to deal with form state management that I could use independently.

As part of this work, I explored a purely functional and strongly typed approach. I leveraged the amazing fp-ts library for the app, and for the form library.

Apologies if you're not massively familiar with fp-ts or functional programming in general, I hope that the ideas I'm showing here will have merit irrespective of the actual implementation.

What does it look like?

Whenever I build an abstraction like this, I always list out the requirements and then sketch out what the external API should look like. Usually I'll go through a few iterations before settling on the final API, and I do this inside my editor before I implement the internals. I find that by doing this, I start to build up an intuition for what the internal implementation should look like.

Here's a quick video showcasing what it's like to use of the library to build a simple form:

And here's the code:

// we'll define a schema of our form fields as a simple object type

type Fields = {

name: string; // a simple scalar value

nickname: string;

location: string;

avatar: ImageModel; // application-specific data types should be supported too, i.e. we'll have a CameraField component that produces an `ImageModel`.

};

type ImageModel = {

uri: string;

width: number;

height: number;

};

const {

submit, // submit should run the validation and let the caller know whether everything's valid or not

registerTextInput, // a function that binds a text field to the form. Provides state management for the field as well as error, touched state and any other information the field needs. MUST be strongly typed to the schema i.e. registerTextInput('name') works, but 'nameee' and 'avatar' throw compile time errors.

registerSinglePickerInput,

registerCameraField, // only keys in the schema that match the camera field's value requirements can be registered, i.e. registerCameraField('avatar') will work, whereas 'location' will not.

} = useForm<Fields>(

// the first argument will be the default values for the form

{

name: "",

nickname: "",

location: "",

avatar: {

uri: "",

width: 0,

height: 0,

},

},

// the second argument will be our validation constraints for each field. We'll use Valley to actually implement validation: https://github.com/josephluck/valley

{

name: [constraints.isRequired, constraints.alphaNumeric], // multiple constraints are supported

nickname: [constraints.atLeastLength(5)],

location: [], // optional fields are supported

avatar: [constraints.isValidImageModel],

}

);

const onSubmit = () => {

// validation uses fp-ts

pipe(

TE.fromEither(submit()),

TE.chain((values) => save(values)) // submit returns the values of the form for ergonomics

);

};

return (

<FormContainer onSubmit={onSubmit}>

<TextField label="Name" {...registerTextInput("name")} />

<TextField label="Nickname" {...registerTextInput("nickname")} />

<PickerField

label="Location"

multiValue={false}

options={locations.map((value) => ({

value,

label: location,

}))}

{...registerSinglePickerInput("location")}

/>

<CameraField

label="Picture"

type="plant"

{...registerCameraField("avatar")}

/>

</FormContainer>

);

There are a few key things I would like to point out from the above:

Type safety

I focused on ensuring that the useForm hook is fully type safe. And I don't just mean that useForm returns type safe functions and values (i.e. type RegisterTextInput = (key: string) => TextFieldProps), but rather the type system knows about the schema passed to the hook (i.e. type RegisterTextInput = (key: StringKeys<Fields>) => TextFieldProps).

I'm a strong believer that leveraging the type system to this extent greatly reduces the number of bugs and inconsistencies that build up over time in a code base. In addition, refactoring is much and safer. Types also serving as a form of living documentation for developers - not to mention the editor autocompletion which we'll get to later on.

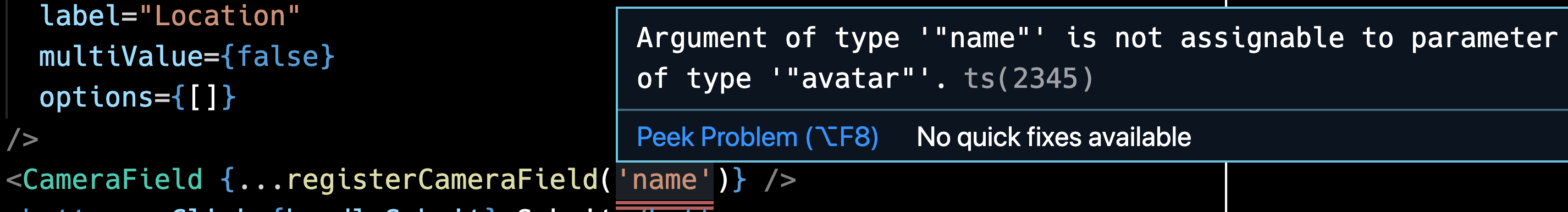

Here's an example of a type error when using an incompatible key when registering a field:

registerCameraFieldknows the keys in the schema that are of the type that<CameraField />accepts.

Developer experience

With everything I build, I strive to deliver the best developer experience I can. There are many different and important things that make for a great developer experience, however one that I find incredibly useful is to leverage TypeScript's ability to provide editor auto completion for domain specific types.

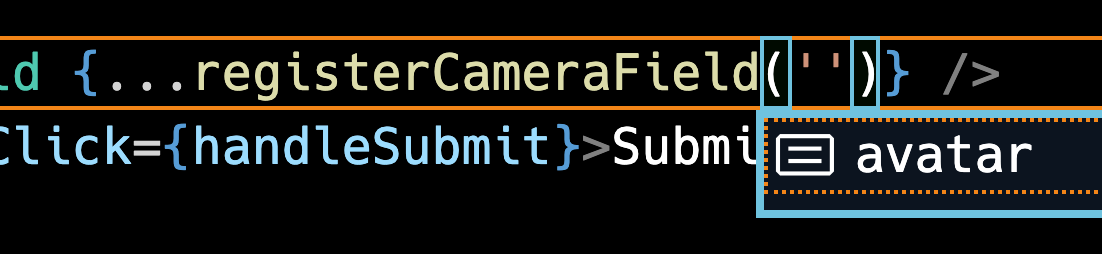

Here's a couple of examples of editor autocompletion when registering a image fields:

Because

useFormis so strongly typed, editors with TypeScript intellisense will give us a choice of keys that are compatible for registration with the<CameraField />

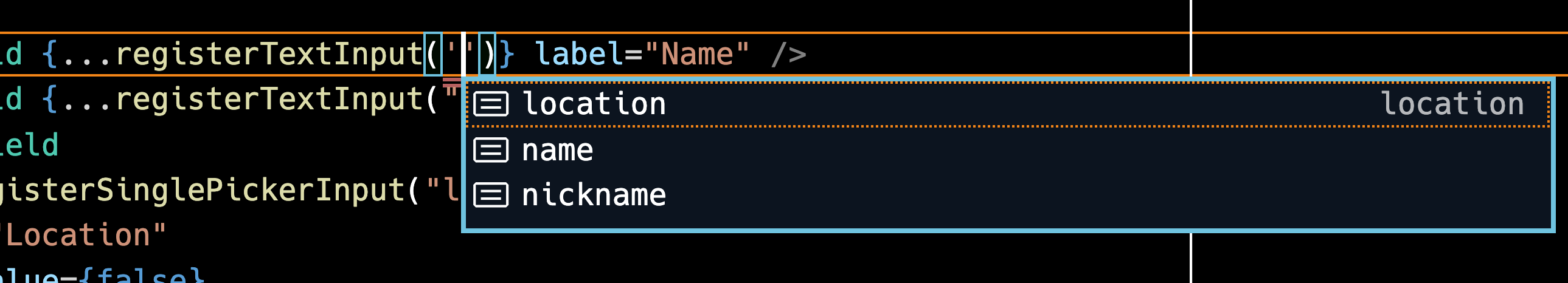

Here's another example for string fields:

Similarly, editors gives us a choice of keys that are compatible for registration with the

<TextField />

Separation of concerns

The form state management (and validation) are grouped together in a single module and is managed independently from the UI components. As an example, the <TextField /> has no knowledge of the internal workings of the library, all it cares about is receiving a value and letting the parent component know when the value changes (as well as displaying error messages).

This separation of concerns means that the form state management and the <TextField /> component can change independently, as they have no direct dependency on one another - apart from the form state management's registration functions return the props that the UI components expect.

In addition, the form state management and validation are completely separate to the business logic of what happens when the data is actually used (i.e. what happens when the form is submitted). The library provides a submit function that simply runs validation and provides the current values of the form fields, but it does not actually do anything with the data, not does it provide loading states or anything else. It's intentionally scoped to manage form state and validation really well and nothing more.

Constraints

The final thing I would like to point out is that not only are the fields themselves fully type safe to the schema, but the validation constraints are too.

The library uses Valley (a validation library I wrote) for it's validation, which expects strongly-typed constraint functions. These strong types are fed through from the schema such that it's only possible to provide constraints that are typed to expect the same value as the schema defines.

I find this to be a really important part of both the developer experience and the safety afforded by the library as it allows the developer to be confident that they are configuring their form correctly by ensuring that only compatible constraints used. I liken this level of TypeScript usage to bowling with the guard railes up - you have no choice but to on target (you might not get a perfect strike though 😉).

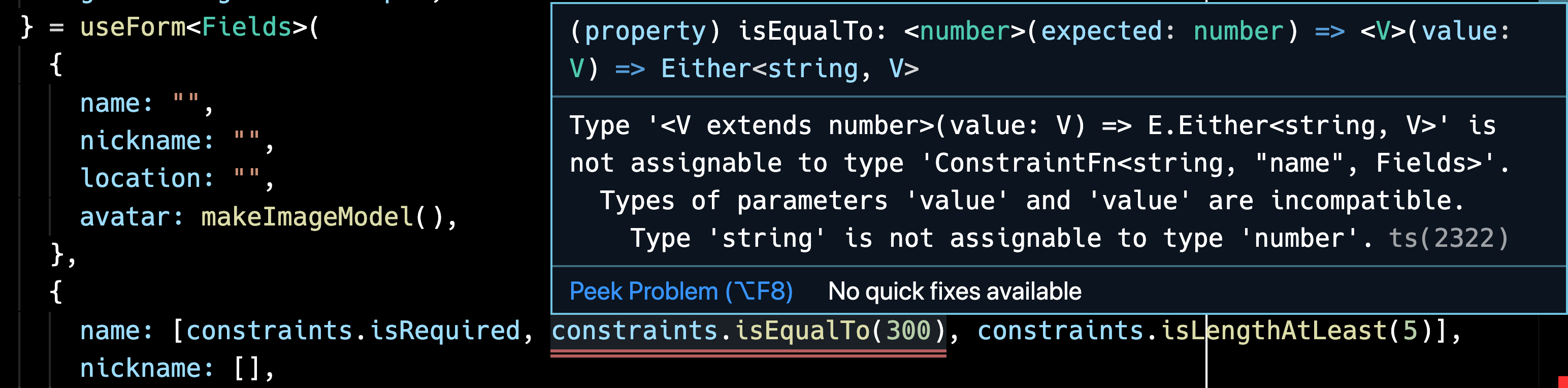

Here's an example of the type error when using an incompatible number constraint against a string field:

The library enforces the constraints for the schema to be compatible with the schema's values. Here we see a compile time error because we've uses a constraint that operates on numbers against the

namekey in the schema, which is a string - only string constraints are permitted.

The implementation

Now we'll dive in to the implementation, which I will show you first and then attempt to explain key areas of interest:

import { FieldConstraintsMap, makeValidator } from "@josephluck/valley/lib/fp";

import * as E from "fp-ts/lib/Either";

import * as O from "fp-ts/lib/Option";

import { pipe } from "fp-ts/lib/pipeable";

import { useState } from "react";

import { TextFieldProps } from "../components/text-field";

type Fields = Record<string, any>;

type FilterType<O, T> = { [K in keyof O]: O[K] extends T ? K : never };

type FilterTypeForKeys<O, T> = FilterType<O, T>[keyof O];

export function useForm<Fs extends Fields>(

initialValues: Fs,

constraints: FieldConstraintsMap<Fs>

) {

type StringKeys = FilterTypeForKeys<Fs, string>;

const doValidate = makeValidator<Fs>(constraints);

const [values, setValues] = useState(initialValues);

const [touched, setTouched] = useState(() =>

getInitialTouched(initialValues)

);

const [errors, setErrors] = useState<Record<keyof Fs, string>>(() =>

pipe(

doValidate(initialValues),

E.swap,

E.getOrElse(() => getInitialErrors(initialValues))

)

);

const validate = (

currentValues: Fs = values

): ReturnType<typeof doValidate> =>

pipe(

doValidate(currentValues),

E.mapLeft((e) => {

setErrors(e);

return e;

}),

E.map((v) => {

setErrors(getInitialErrors(initialValues));

return v;

})

);

const setAllTouched = () => {

setTouched(

Object.keys(initialValues).reduce(

(acc, key) => ({ ...acc, [key]: true }),

initialValues

)

);

};

const setValue = <Fk extends keyof Fs>(fieldKey: Fk, fieldValue: Fs[Fk]) => {

const newValues: Fs = { ...values, [fieldKey]: fieldValue };

setValues(newValues);

validate(newValues);

};

const setValuesAndValidate = (vals: Partial<Fs>) => {

const newValues: Fs = { ...values, ...vals };

setValues(newValues);

validate(newValues);

};

const submit = () => {

setAllTouched();

return validate();

};

const reset = () => {

setValues(initialValues);

setTouched(getInitialTouched(initialValues));

setErrors(getInitialErrors(initialValues));

};

const registerBlur =

<Fk extends keyof Fs>(fieldKey: Fk) =>

() => {

setTouched((current) => ({ ...current, [fieldKey]: true }));

};

const registerOnChangeText =

<Fk extends keyof Fs>(fieldKey: Fk) =>

(value: string) => {

setValue(fieldKey, value);

};

const registerTextInput = <Fk extends StringKeys>(

fieldKey: Fk

): Partial<TextFieldProps> => ({

value: values[fieldKey],

error: errors[fieldKey],

touched: touched[fieldKey],

onBlur: registerBlur(fieldKey),

onChangeText: registerOnChangeText(fieldKey),

});

return {

values,

touched,

errors,

validate,

setValue,

setValues: setValuesAndValidate,

reset,

submit,

registerTextInput,

};

}

const getInitialTouched = <Fs extends Record<string, any>>(

fields: Fs

): Record<keyof Fs, boolean> =>

Object.keys(fields).reduce(

(acc, fieldKey) => ({ ...acc, [fieldKey]: false }),

fields

);

const getInitialErrors = <Fs extends Record<string, any>>(

fields: Fs

): Record<keyof Fs, string> =>

Object.keys(fields).reduce(

(acc, fieldKey) => ({ ...acc, [fieldKey]: "" }),

fields

);

Note, in the code above, I've only included support for text fields. You can imagine that this library could support any number of form field types, depending on the application. For example, Urban Jungle has a form field component for taking a picture and uploading it. This field is highly specific to Urban Jungle, and being able to have first-class form state management and validation for it truly highlights the power of this approach.

How the types work

The first thing I'd like to highlight is how the type safety works from the schema. You'll notice that there's a generic type argument to useForm which is constrained to a Record<string, any> type. This constraint ensures that the form hook only manages objects. The generic type argument can be inferred from the initial data argument, but it's advised to manually provide an explicit type.

Built up from the generic type, additional types are created such as type StringKeys. These additional types are used in the registration functions to strongly type the name of the field that should be registered according to compatible keys in the schema.

Registration functions

One thing I quite like about this library is the ease in which you can bind values, callbacks, error states etc to a form field component. For example, <TextField {...registerTextInput('name')} /> is all you need to tie up validation and state from the library to a form field.

The registration functions are typed to take a key from the schema that matches the type of input, aka, string for <TextField /> components via registerTextInput(), number for <NumberField /> components (via registerNumberInput()), etc. The registration functions return an object of props that the respective component uses. In the libraries implementation, you'll notice the prop types are imported and are the return types of the registration functions.

One of the great aspects of the registration functions is that if the requirements of the field component change, the compiler will let us know and we can ensure that the form state management conforms to what the components are expecting.

Unfortunately, as the requirements for these registration functions are heavily dependent on the prop requirements of custom components, it's not viable to open source the library.

Validation

You'll notice a doValidate function that uses Valley's makeValidator factory function. Valley is a validation library I made (that I wanted to use for Urban Jungle), however it would be trivial to swap out Valley for another validation library. yup would be a popular alternative.

I chose to use Valley as it implements fp-ts compatible validation constraints requirements using Either and TaskEither which Urban Jungle uses heavily for controlling business logic in a pure and functional way.

The bulk of the validation logic resides in the validate function which simply calls doValidate and sets errors in the state (if there are any).

Wrapping up

I hope this article has shown you the way I think about abstracting things away by prioritising developer experience, type safety and maintainability of the outside use.